Microcontroller architecture and Memory technology¶

Microcontroller architecture¶

This lecture describes the common building blocks of a microcontroller, and how they interact with each other. It is generally better to combine as many as possible components in a single chip. The advantages of integration are:

Cost: IC packages, PCB area, and PCB assembly are all major cost items that can be reduced with integration of components in a single device.

Easy development: You don’t need to worry about interfacing external components and the related noise coupling or interference problems. Accessing an ADC is as easy as writing and reading a few special function registers when the ADC is available as an on-chip component of the microcontroller. On the other hand, if you end up using an external ADC component, then you need to find solutions to several design requirements such as, ADC power supply, interface protocol, reserving I/O pins on the microcontroller, and routing I/O connections on the PCB.

Some well known processors¶

The instruction set architecture (ISA) of the processor describes the main processing capabilities of a microcontroller. Usually a microcontroller is labeled with a core name that identifies the processor ISA (e.g. … . . controller with ARM core or … . . controller with 8051 core). Note that the ISA determines the main programming features and requirements of a processor. The hardware implementation may vary from an IC manufacturer to another. Following is a list of some common processor architectures used in microcontrollers.

AVR (Atmel): A large variety of Harvard architecture microcontrollers manufactured by Atmel (Atmel has been consumed by Microchip). The Atmega328p is one example on an AVR controller, and is the one used in the application work of this course.

PICXXX (Microchip): PIC (Peripheral Interface Controller) is a family of Harvard architecture microcontrollers manufactured by Microchip Technology, first introduced in 1976. PIC microcontrollers have been widely used for both industrial applications and hobby purposes.

8051 (Intel): A Harvard architecture 8-bit microcontroller series developed by Intel in 1980 for use in embedded systems. Today, a large variety of faster and enhanced 8051-core microcontrollers are produced by more than 20 independent manufacturers.

68XX, 680X0 (Motorola): The 68xx is an 8-bit microprocessor family introduced by Motorola starting in 1974. The MC6801 and MC6805 were commonly used as microcontrollers in automotive industry. The Motorola 6809 introduced in 1977 had some 16-bit features. The Motorola 680x0 is a family of 32-bit processors that were popular in personal computers and workstations until the mid-1990s. Descendants of the 680x0 family processors are still widely used in embedded applications.

ARM (ARM7, ARM9, ARM11 - ARM Holdings): ARM architecture is the most widely used 32-bit ISA in terms of numbers produced. ARM Holdings itself does not manufacture any processors but they license ARM ISA to independent manufacturers. ARM processors dominate the mobile and embedded electronics market (90% of all embedded 32-bit RISC processors in 2009), because they are suitable for low power applications as relatively low cost, simple, and small microprocessors.

x86 (386, 486, Pentium, … - Intel): The term x86 refers to a family of ISAs based on the Intel 8086 CPU introduced in 1978. More specifically, x86 implies compatibility with the instruction set of 32-bit 80386. x86 processors are not widely used in embedded systems.

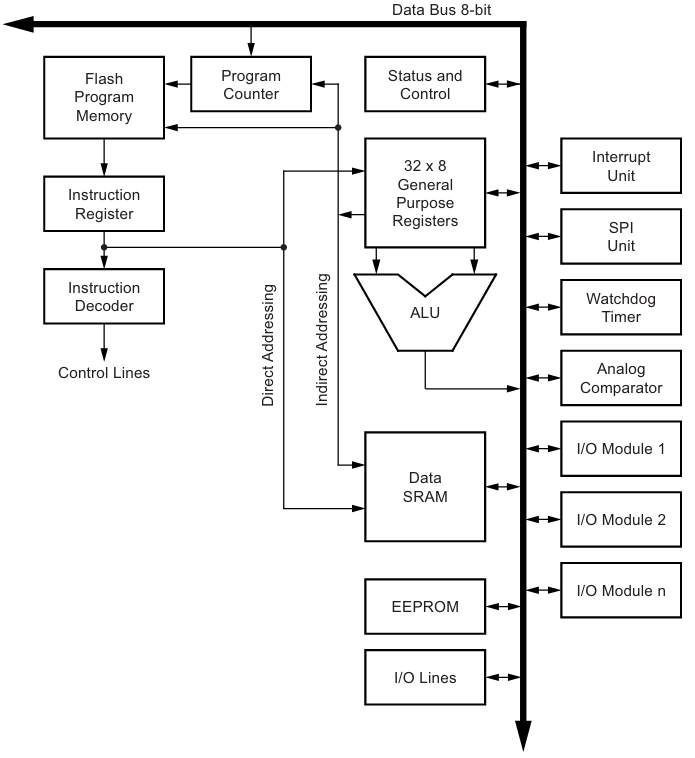

Atmega328p core architecture¶

Memory Requirement of an Embedded System¶

A stand-alone computer requires two types of memory. First, a non-volatile memory is necessary to store the program instructions and other permanent information required for execution. The non-volatile memory does not lose the stored information when power is turned off. The second type of memory is the volatile memory to store temporary or dynamically changing information during program execution.

Non-volatile memory requirement:

Program storage

Read-only tables, such as calibration data, system control parameters, user settings that should be saved when power is turned off.

At least 20% safety margin for the additional memory that may be required for future corrections and upgrades.

Volatile memory requirement:

Variables

I/O buffers

Other data structures, such as stacks and queues.

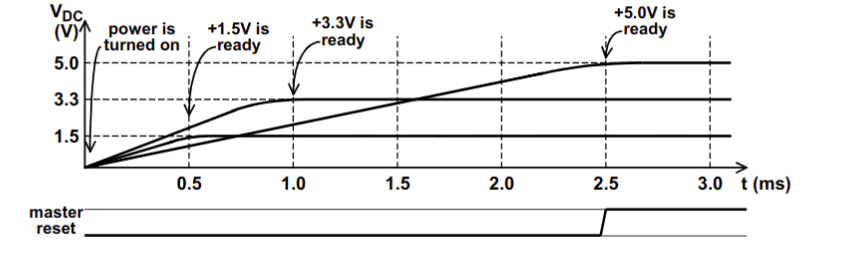

Reset Circuit¶

Active electronic devices require all supply voltages to be within specified limits to operate properly. The device behavior is unpredictable if a supply voltage is outside the specified range. A power-on-reset (POR) signal is required to make sure that all components of a system are in a known idle state until the supply voltages reach the specified operation limits. Supply monitors (also called “power monitor” or “voltage monitor”) are the dedicated circuits that generate a master reset signal according to the supply conditions. These are the functions of the master reset signal:

Suspend all operations while the voltage regulators are ramping up until the supply voltages reach the specified operation limits (power-on-reset).

Initialize state of sequential logic circuits.

Stop and re-initialize circuit operations if a fault condition occurs at the supplies.

Consider an embedded system that requires three voltage regulators to supply DC power for the following purposes:

+1.5 V supply for processor core and memory

+3.3 V supply for I/O with peripherals

+5.0 V supply for sensors and drivers

Clock Generator¶

Clock generator provides the clock signal for all sequential circuit operations. Most systems use a single clock source as a reference and necessary clock frequencies are derived from this reference clock using simple frequency dividers or phase lock loops (PLL). The precision of clock timing depends on the requirements of a particular application. Generation of a pulse-width modulation (PWM) output, for example, can tolerate large variations in the clock frequency. The effective value of a PWM output is determined by the duty cycle which is independent of the clock driving the PWM circuitry as long as the clock frequency remains relatively constant in each PWM cycle. The timing precision of a clock signal used for speed measurements on the other hand, should match the accuracy of the measurements. There are strict frequency matching requirements for I/O channels that rely on independent clock signals as frequency references.

A microcontroller may require an external clock generator or it may have on-chip circuitry that supports a frequency resonator. These are the typical specifications for a clock generator:

Maximum deviation from target frequency specified in +/- ppm (particle per million). If you purchase a 10 MHz resonator specified with +/-50 ppm accuracy, then you will obtain a resonance frequency between 9,999,500 and 10,000,500 Hz.

Temperature dependency of oscillation frequency specified in ppm/ºC. The maximum frequency deviation guaranties the oscillation frequency range at a constant temperature (usually 20 or 25ºC). The temperature dependency adds on to the frequency uncertainty according to the temperature variations.

Jitter, or the timing error between clock cycles: Having 10,000,000 clock cycles in one second does not necessarily mean that each clock cycle will be exactly 100 ns. Jitter is the measure of timing error from one clock interval to another, that can be an important factor when matching reference frequency of communication channels.

I/O PORTS, Channels, Buffers¶

I/O ports on a microcontroller provide general-purpose access capabilities to external devices. These ports can be simple I/O pins that can be read or written by the core processor or they can be combined with more complex interface options. Some examples of these interface options are:

Independent access to individual I/O pins as well as of 8 or 16 pin groups.

Built in buffering functions for continuous data transfers.

Direct memory access to or from the port pins for high-speed communication with external devices without using processor time.

One should be careful about determining the number of available I/O pins on a microcontroller. Almost all microcontrollers assign multiple functions to many of the I/O pins. An I/O pin required as an external interrupt input or as an analog interface pin will not be available for general-purpose I/O functions.

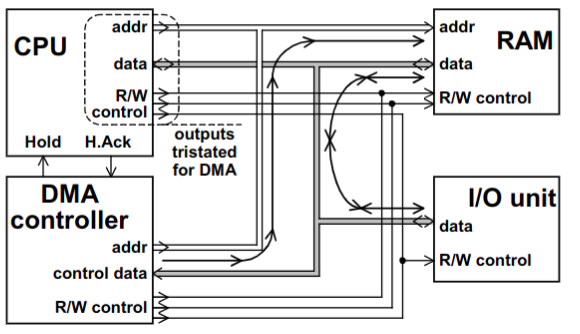

Data transfers between the RAM and I/O units or other storage devices may take long processing times depending on the amount of data to be transferred. For example, if the CPU handles a sequence of data transfers from an I/O unit to the memory, then it performs several operations to transfer each word of data:

Read data from the I/O unit into the CPU register.

Write data from the CPU register to the RAM.

Increment the pointer for the target address in the RAM.

Decrement the byte/word counter.

Check the byte/word count and go back to step-1 if there is more data to be transferred.

As an alternative, a direct memory access (DMA) controller can be used to speed up the data transfers. DMA controller takes over management of address, data, and R/W control lines after CPU tristates its outputs. DMA controller generates the required address sequence for memory and arranges timing of the control signals for memory and I/O unit. Data words are transferred directly between the memory and the I/O unit. It takes just one R/W memory cycle to complete the transfer of a data word. Direct memory access is an order of magnitude faster compared to the CPU operations that take10s of memory R/W cycles for each data transfer. CPU programs the DMA controller writing starting memory address, number of data transfers, and other necessary information into the controller registers. DMA controller sends a “Hold” signal to the CPU asking for release of memory control when it is ready to start the transfer sequence. CPU replies with a “Hold Acknowledgement” after it tristates its outputs. DMA controller returns control of memory back to the CPU after it completes the data transfers.

Serial I/O¶

A serial interface will be slower compared to a parallel bus operating at the same clock frequency. Whenever you don’t need the combined speed of all the data bits in parallel, a serial interface is preferable because of these advantages:

It requires less number of pins. A serial interface uses 2, 3, or 4 connections, so it will require 2-4 pins on transmitter and receiver ends. An 8-bit parallel interface on the other hand, would require 10 or more connections between the transmitter and receiver ends. Less number of pins means smaller and cheaper IC packages.

PCB design will be easier for a serial interface, and it will save PCB area as well. Simply, you will route 3 connections instead of 10.

Serial interface will require less power. A serial interface will eventually use more-less the same amount of average power to transmit the same number of bits, but the instantaneous power requirement will be different. If you decide to use a parallel interface, then you had to be prepared for the worst case where all data lines switch from 0 to 1 at the same instant.

Save on noise. Just as simultaneously switching 8 data lines requires more power, it will also generate more noise on your PCB.

Two different types of serial I/O interfaces can be found on microcontrollers or embedded processors. The first type of serial interfaces are for “on-board” or “in-box” communication between the components of a single unit. The commonly used examples of on-board serial communication interfaces are SPI, uWIRE, and I2C. The second type of serial I/O interfaces are used for box-to-box communication between the independent design units through cables. The typical examples of box-to-box serial interfaces are USART (Universal Synchronous Asynchronous Receiver Transmitter, RS-232, RS-422, etc.), USB, and Firewire (IEEE 1394). Another advantage of serial interfaces in box-to-box communication is the simplicity of the connectors and cables. Long serial transmission cables can be built at a lower cost compared to the cost of parallel data cables that support the similar data transfer rates.

Timers¶

Timers are counters that can be programmed to perform a variety of functions. Following are the typical operation modes and possible applications of timers:

Programmed operation: A timer can be used as an alarm clock to generate predetermined time delays. The microprocessor sets the count limit or initializes the counter and enables the count operation. The timer generates an interrupt when the count limit is reached indicating the end of the programmed delay period. This mode of operation utilizes the internal clock and it does not require an external connection.

Gated or triggered operation: The count operation is controlled by an external signal. There may be several options to start and to stop the counter. In gated mode, the counter is enabled while the external signal is active. A multi-purpose timer allows independent selection of events that start and stop the counter. These events can be a rising or falling edge of the external trigger signal or an internal start/stop command issued by the microprocessor itself. The timer can be programmed to generate an interrupt when the counter stops. The common applications of gated or triggered operation involve any kind of time measurements, such as, measuring revolution time of a motor to detect its rotation speed, or quantification of time-encoded signals.

Clocked operation: The counter clock is supplied by an external signal while the count operation is enabled by the microprocessor or another timer. The typical applications include quantization of frequency-encoded signals, or position information generated by linear or rotational encoders.

Watchdog timers are special-purpose timers dedicated to ensure the proper execution of microcontroller functions. The processor is required to restart the watchdog timer before the preset timer period expires and it repeats this operation as long as the watchdog function is enabled. The program written for the processor includes the necessary statements to restart the watchdog timer periodically. If the processor fails to restart the watchdog timer, then this indicates a major functional failure due to corrupt program memory or some other reason. In this case, the watchdog timer resets the processor, forcing initialization of all microcontroller functions.

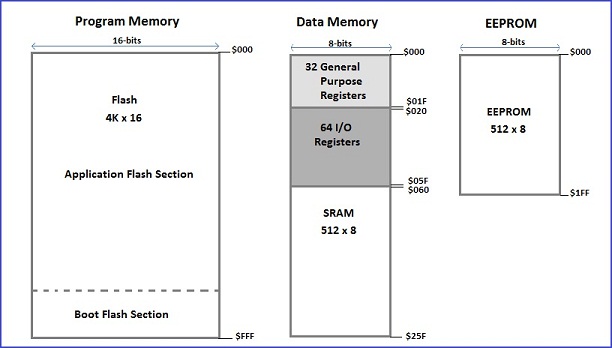

Direct register access on Atmega328p¶

The peripherals of the microcontroller, such as I/O ports, timers, or the interrupt system is configured and controlled by setting special bits in designated areas of memory. An area the beginning of the microcontroller memory address space (from address 0x20 to 0x5F) is reserved for I/O ports, as well as some of the more important peripheral control registers. The regular CPU instructions used to read or write to memory can be used to manipulate these special addresses, but there are also some special instructions (such as the OUT instruction, see: AVR Instruction set manual) available for more efficient manipulation of the registers.

The Atmega328p uses memory addresses of 16 bit, and each CPU instruction is also 16 bit. Since some bits of each CPU instruction must be used for unique identification, it is thus impossible for a single CPU instruction to hold a complete memory address. Since the special I/O register is limited to a small address range it is possible to have instructions where the address is contained as part of the instruction.

Unfortunately the restricted range I/O address space does not have room for all the special control registers, and thus some of them are outside the reach of the special efficient instructions. Regular memory operation instructions must be used to reach them. Additionally in order to best utilize the available bits in each CPU instruction, the value 0x20 is subtracted from the actual memory address to obtain the value to be used in the instruction. That way you start at address 0x00, instead of 0x20.

Normally when we store a value to a variable, e.g. uint8_t a = 5; we do not care about the exact location it is stored in memory, as long as it is stored. For the special I/O registers the exact memory address matters, as the side effects of setting a specific bit (e.g. the side effect that an output port becomes high) will wary depending on the address.

The digital I/O ports of the Atmega328p are utilized by means of three registers. One register (PORTx) is used to write to digital outputs, one (PINx) is used to read digital inputs, and one (DDRx) is used to configure the pin as input, or output. Each register is 8 bits wide, and thus responsible for 8 I/O pins. This grouping of pins is known as a port, and is given a letter starting with A, i.e. PORTA is the output register for the 8 I/O pins of port A.

Functions such as digitalWrite() will access the memory locations of these ports, and manipulate a single bit depending on the parameters to the function. Even though the use of the functions are easier, and more portable than accessing the registers directly, direct register manipulations can be useful since they are faster, and allows us to change multiple pins at once.

The pins 0 to 7 on the Arduino UNO are connected to PORTD (PD0 to PD7 respectively). According to the datasheet PORTD is placed at the address 0x2B. Additionally the data direction register DDRD is placed at 0x2A, and the PIND register is placed at 0x29.

In order to associate a variable name with a specific memory address it is possible to use pointers. A pointer is a variable which holds the location to a memory address, and by using the special dereference operator * we access the memory address instead of the variable. For more details, you can visit Changing the variable through its adress: Pointers.

Memory usage¶

RAM usage at run time¶

After building your program a inspect tool can be used to provide information on the usage of RAM and Flash memory on the microcontroller. This happens automatically in PlatformIO, and the result might look like:

Checking size .pio/build/uno/firmware.elf

Advanced Memory Usage is available via "PlatformIO Home > Project Inspect"

RAM: [= ] 10.6% (used 218 bytes from 2048 bytes)

Flash: [= ] 5.5% (used 1790 bytes from 32256 bytes)

For the Flash usage this is usually the correct value, but for the RAM the situation is more complex. It is possible for an application to change the RAM usage at run time. This happens each time a function is called, or when a function returns. It is also possible to declare more memory as needed, e.g. in order to store some data from a user who interacts with the microcontroller. Dynamic memory allocation is typically discouraged on microcontrollers which has small amounts of total RAM available, but still it should be apparent that the RAM usage can be a complex thing to analyze in some cases.

Stack overflow¶

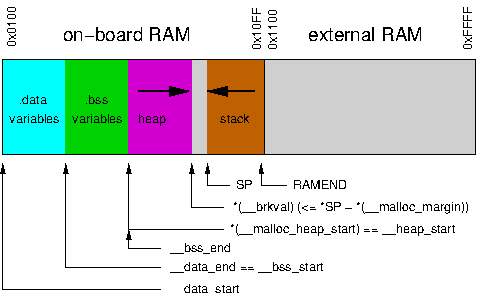

The data memory (RAM) of the microcontroller is divided in to several portions. First we have the .data, and the .bss (Block Started by Symbol) sections at the lower addresses in memory. The .data section contains initialized global variables, and local variables declared as static. The .bss section is for the uninitialized variables in the same two categories. The .data and .bss sections do not change during the execution of the program.

After that follows the dynamic portions of the memory, the stack and the heap which may change size as the program executes. The stack grows down from the top of the memory, and is used for storing data in functions as they are called, e.g. variables local to functions. The heap grows up from the bottom of the memory and is used for dynamically allocated memory.

If the stack grows so large that it runs in to the heap area, you have what is known as stack overflow. In this case the behavior of the microcontroller will be unpredictable. It is therefore important to have some free space in RAM for the stack to grow or shrink as functions are called or returning.

An additional exercise on determining the stack usage can be found at Exercise: determine stack usage.

Little or big endian¶

Endianness describes the ordering of bytes when storing numbers of more than 8 bits. Almost all modern computers organize the memory in chunks of 8 bit, called bytes. If the ordering is big endian, the most significant byte is stored first, while little endian means that the least significant byte is stored first. This naming convention might seem illogical at first, but endian refers to the end which comes first, not the end of the number in memory. Hence big endian means that the big end (most significant part) comes first.

The endianess is typically not something you need to consider while developing software on a given microcontroller, since the C compiler takes care of the details. It can however become important when interfacing several microcontrollers to each other. It is a fundamental concept which should be understood by anyone involved in software development.

In order to check if the microcontroller is little or big endian one may force the compiler in to considering a pointer to a 16 bit value as a pointer to an 8 bit value. By reading the value that the pointer is pointing to, only 8 bits are returned, and these would be the 8 bits that are stored first in memory. If the bits returned are the most significant bits of the original number,

1#include <Arduino.h>

2

3uint16_t test_number = 0xabcd;

4

5uint8_t *test_number_pointer = (uint8_t*) &test_number;

6

7void setup() {

8 Serial.begin(9600);

9

10

11 Serial.print("First byte: ");

12 Serial.println(*test_number_pointer, HEX);

13 Serial.print("Second byte: ");

14 Serial.println(*++test_number_pointer, HEX);

15

16

17}

18

19void loop() {

20 // put your main code here, to run repeatedly:

21}

> Executing task in folder little-or-big-endian: platformio device monitor <

--- Available filters and text transformations: colorize, debug, default, direct, hexlify, log2file, nocontrol, printable, send_on_enter, time

--- More details at https://bit.ly/pio-monitor-filters

--- Miniterm on /dev/ttyACM0 9600,8,N,1 ---

--- Quit: Ctrl+C | Menu: Ctrl+T | Help: Ctrl+T followed by Ctrl+H ---

First byte: CD

Second byte: AB

The first byte is 0xCD which is the least significant byte, while the second byte is 0xAB which is the most significant byte. This suggests that the CPU is little endian (the little end of the number comes first), and we know from the datasheet that the AVR CPU is little endian.

Non volatile storage in EEPROM¶

If you have some value in your program which you would like the microcontroller to remember the next time it boots, you have the option to store it to the EEPROM. The Atmega328p has 1 kilobyte of EEPROM.

1#include <Arduino.h>

2#include <EEPROM.h>

3

4

5void setup() {

6 Serial.begin(9600);

7

8 uint8_t boot_count = EEPROM.read(0);

9 EEPROM.write(0, boot_count + 1);

10

11 if(boot_count < 5){

12

13 Serial.println("The board has booted less than 5 times");

14 }

15 else{

16

17 Serial.print("The current boot count is:");

18 Serial.println(boot_count);

19 }

20}

21

22void loop() {

23

24 // Be careful with write operations to the EEPROM in loop

25 // If they run continuosly it might wear out the EEPROM

26}

Exercise: store ADC readings in EEPROM¶

Connect a push button with pull-down resistor to pin 3, and a potmeter to analog input A0

Write a program which reads the value on analog input A0, and print it on the UART.

Add prober edge detection, and debounce routines for the push button.

Add the functionality to store the current ADC reading to an array by pushing the button. The 10 most recent readings should be stored, i.e. if the memory already holds 10 readings, the oldest reading should be dropped. Print all readings to the UART at a rate of 1 second.

Add the functionality to store the array in EEPROM each time the button is pushed.

Memory technology¶

No, floppy disk is not a 3D printed save button

Common Non-volatile Memory Devices¶

ROM (Read-Only Memory): The term, ROM, strictly meant “read-only memory” as it was used some decades ago. The data stored in a ROM could not be modified by any means. But today, ROM may refer to all types of non-volatile memory included within an embedded computer system. The data stored in a ROM remain unchanged or “read-only” during the normal program execution, but the memory contents can be modified slowly or with difficulty when it is necessary. The following is a list of other related memory devices:

PROM (Programmable ROM): Memory contents can be written only once by fusing (blowing up) or anti-fusing the connections in the device applying high voltages.

EPROM (Erasable Programmable ROM): Memory contents can be written using a programming device. An EPROM can be erased by exposing it to strong ultraviolet light through the transparent window placed on top of the chip.

EEPROM (Electrically Erasable Programmable ROM): A version of EPROM where memory contents can be erased electrically instead of using ultraviolet light.

FLASH Memory: FLASH memory is a kind of EEPROM that is commonly used as non-volatile memory on the microcontrollers available in the market today. The EEPROMs other than FLASH are erasable in small blocks (i.e. byte by byte). Large blocks of data can be erased and written simultaneously in FLASH memories. This gives a significant speed advantage when writing large amounts of data.

Common volatile Memory Devices¶

RAM (Random Access Memory): Random access means ability to read or write at any memory address as opposed to restricted addressing methods, such as sequential access. The term, RAM, may refer to all types of volatile memory in a computer system. SRAM and DRAM are the two common types of RAM.

SRAM (Static RAM): Memory contents remain intact as long as the power is on. SRAM is the most common type of volatile memory included in a single-chip microcontroller. The cache memories on more powerful CPUs are also SRAM devices.

DRAM (Dynamic RAM): Unlike SRAM, a DRAM device needs to be periodically refreshed to keep the memory contents intact. DRAMs store each bit of data in a capacitor, and the voltage on the capacitor needs to be refreshed because the capacitor charge fades due to leakages. One bit of DRAM storage requires less silicon area compared to one bit of SRAM. DRAM is the choice for large memory requirements since the cost per unit of memory is less for DRAMs

SDRAM (Synchronous DRAM): Data transfers to/from SDRAM are synchronized with a clock signal. Once a memory address is sent to the SDRAM, a sequence of memory locations can be accessed starting at the specified address.

DDR SDRAM (Double Data Rate SDRAM): SDRAM that transfers data at a rate twice as high the synchronization clock frequency by receiving or sending data at both of the rising and falling edges of the clock.

Flash memory¶

Flash memory is a type of non volatile memory. Flash memory has it’s name from the requirement that one has to erase a whole block of memory if one or more bits of the block has to be changed from zero (0) to one (1). This is a so called Flash erase.

Initially (or straight after a Flash erase) all the bits of a flash memory block are one (1), and you only program the bits which have to be zero (0). As soon as a zero (0) bit has to return to the one (1) state however, you must perform a Flash erase.

There is no physical limitation that forces us to use a full block erase, but the memory is designed in this way (the transistors are connected in such a way that this is the only possibility). The reason for doing this is that the erase cycle is a relative slow operation, and thus there is a speed gain in erasing many bits at once.

A Flash memory supporting single byte (or bit) erase is called a EEPROM. But in order to achieve this the circuit for each bit is more complex, and hence more expensive.

Each bit in a Flash memory consists of one transistor, specifically a floating gate MOSFET. The floating gate holds a negative charge when the bit is programmed, and neutral charge when it is not programmed. The negative charge prevents current from flowing through the transistor when a read voltage is applied, thus zero current is interpreted as a logic zero (0) [].

Random access memory¶

Random access memory (RAM) refers to memory where individual bytes of data may be read and modified without affecting other parts of the memory.

Static RAM¶

Static RAM (SRAM) is a form of volatile memory. Each bit requires six transistors, and the read and write times are equal.

Dynamic RAM¶

Dynamic RAM (DRAM) is a form of volatile memory. Each bit in a DRAM memory consists of one transistor and one capacitor.

The bits must be refreshed, i.e. the capacitor must be recharged at certain intervals if it is storing a one (1), to avoid loosing the information. The JEDEC (Joint Electron Device Engineering Council) standard states that the refresh rate should be less than 64 ms.

DRAM is normally very fast when compared to Flash memory, and has equal read and write speeds.

EEPROM¶

Hard disk drives¶

A hard diske drive uses magnetic storage to store data on a rotating platter. It has a moving read and write head.